April 08, 2025

BY ESHERU KWEKU

The British media has long been heralded as a pillar of democracy, entrusted with the responsibility of informing the public, holding power to account and reflecting the full breadth of society. Yet, behind the glossy pages of national newspapers and the polished sheen of broadcast studios lies a stark reality: British media is neither diverse nor representative of the public it serves.

Despite the UK's multicultural society, the upper echelons of British media remain largely homogenous, dominated by white men and women who are overwhelmingly privately educated. According to data from the National Council for the Training of Journalists (NCTJ), as of 2022, 88% of journalists in the UK were white, with only 12% coming from Black, Asian, or minority ethnic backgrounds.

This disparity is even more pronounced in senior positions. For instance, a study by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism found that Black journalists represent a mere 0.2% of the journalistic workforce, despite constituting 3% of the British population.

The pathway to media power in the UK is often paved through elite institutions. Studies have shown that around half of the top editors in British newspapers were privately educated, compared to just 7% of the UK population. Oxbridge graduates continue to flood newsrooms, bringing with them a worldview shaped by privilege and exclusion from the lived experiences of many Britons.

This lack of representation directly impacts how stories are framed and which narratives dominate the headlines. It explains why certain communities are consistently portrayed through a deficit lens viewed as problems to be solved rather than active agents within society.

For example, stories about immigration, crime, or protests are frequently sensationalised, playing into harmful stereotypes while failing to contextualise issues within structural inequalities or historical injustices. Meanwhile, systemic racism, austerity’s impact on working-class communities, and other pressing issues are often downplayed or ignored altogether.

This crisis of representation has not gone unnoticed by the public. Trust in the media is alarmingly low, particularly among minority and working-class audiences who feel alienated by coverage that does not reflect their realities. The dominance of certain voices and perspectives erodes public faith in journalism as a neutral arbiter of truth and accountability.

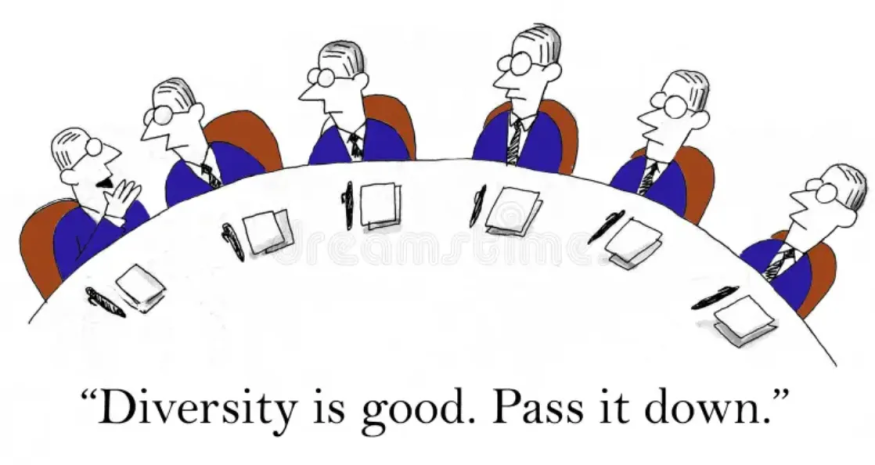

In response to mounting criticism, many media organisations have rolled out diversity and inclusion initiatives. However, critics argue that these efforts often focus on superficial change diversity panels, unconscious bias training, or short-term schemes without addressing the structural barriers that prevent genuine progression into senior leadership roles.

A truly representative media must go beyond tokenistic hiring and foster an environment where diverse talent can thrive and lead. This includes rethinking recruitment pipelines, supporting working-class and minority journalists into leadership roles, and creating editorial cultures where all perspectives are valued.

It also requires media consumers to demand better. Readers, viewers, and listeners must hold outlets to account, challenge bias and uplift independent media organisations that prioritise inclusion and authenticity.

Until the British media fully reflects the society it reports on, it will continue to tell only a fraction of the story.